From China to the Atlantic, the foundations of the earth were shaken,—throughout Asia and Europe the atmosphere was in commotion, and endangered, by its baneful influence, both vegetable and animal life. The series of these great events began in the year 1333, fifteen years before the plague broke out in Europe : they first appeared in China.

– J.F.C. Hecker, MD, Black Death (1832)

Where did the Black Death come from? Why was it so deadly? Was it confined just to Europe? How did it spread? What were its symptoms? How did people die?

I’m sure these questions have come to many peoples’ minds in recent years. A close look at historical accounts reveals a startling reality that mainstream narratives rarely mention, much less explore. This reality is pertinent not only to 14th century events, but is part of a larger history of the globe that for the most part has gone unperceived and uncontemplated, especially in acedemia and popular retellings of the past.

In this article, I’ll put together the peices, each one of them a pardigm shifting revelation.

OVERVIEW

Introduction: Global Cataclysms of Past Ages

A profound realization

Ancient cometary impacts, the end of the dinosaur era and the end of the Wooly Mammoth

Cataclysmic events between 2350 BC and 540 AD

Supervolcanoes and global cooling

Diverse traditions tell of widespread destruction and renewal

13th and 14th Century Events and the Black Death

Volcanoes, Comets, Earthquakes and Plague

The Wolf Solar Minimum (1280-1350),

Baillie’s “New Light on the Black Death”

Hecker’s account of natural disasters in China

Climate disruption and floods in South America and India

Millenial Floods in Europe 1342-1343

Black Plague in Europe

14th Century Biological Warfare?

The Great Fruili Earthquake of 1348

Symptoms of the Black Death

Problems with the Y. Pestis hypothesis

“Plague”, a non-specific ailment

-Summary: Points to Remember

-Timeline leading up to the Black Death

-Appendix: Hecker’s Chronology

A 14th century engraving depicts a man with the plague with spots all over his body (unlike modern day bubonic plague where “buboes,” or swellings, are said to appear in the groin or armpits).

Note what appears to be a depiction of extreme lightning in the background. Trees are bowed over, presumably from heavy winds. The people seem to be leaving the town behind which appears to be on fire, with some of the houses falling over. No one appears too concerned about getting away from the man with the plague.

I first came across the abundant evidence that the Black Death of the mid 14th century occurred in tandem with extreme environmental upheaval while ploughing my way through Dawn Lester and David Parker’s thick volume, What Really Makes You Ill: Why Everything You Thought You Knew About Disease Is Wrong.

While writing a review, I chanced upon Sasha Dobler’s thoroughly researched, densely packed book, Black Death and Abrupt Earth Changes (2017/2018). Dobler described how extreme climatic disruptions beginning toward the end of the 13th century brought an end to the Medieval Climate Optimum—a period of prosperity and growth in population—and led to decades of suffering and great mortality across Europe long before the mid 14th century climax during the years of the Black Death in Europe.

..while there is an absolute paucity of evidence of the establishment’s caricature of the Black Death (1348-51) being caused by a bacterium spread by rats and fleas, there is abundant evidence from multiple disciplines that it coincided with extreme cosmological and geological perturbations, confirmed by widespread contemporary eye-witness reports of comets, earthquakes, famine, flashes of light in the sky, foul smelling gases from the air, from the ground, and the sea, and even trees covered with [ dust].

—What Really Makes You Ill book review, by Tobin Owl (Jan. 2022)

It was only in recent weeks that I learned through an article titled Comets or Contagion that similar catastrophic cosmological, geological and climactic events had preceded the 6th century Justinian plague—the second worst plague of the last 2 millennium, comparable in its devastation to the Black Death. That discovery reignited my interest in the subject and led to the current series. Part 1 of this series dealt with questions around plague in general and the Justinian Plague in particular. If you haven’t seen it I highly recommend beginning there as it will give better context for the current discussion.

COMETS, VOLCANOES, EARTHQUAKES AND PLAGUE Part 1

(Part 2 will focus on 14th century events and Black Plague, also known as the Black Death)

The revelation that extreme atmospheric and geological perturbations had taken place during both time periods—along with other revelations from my researches—suddenly gave me a gestalt view of earth history that had never struck me before in quite the same way, Though seeds had been planted through previous reading, suddenly the grand view lay exposed to my sight, akin to when a fog clears and suddenly a dramatic landscape rolls out into view—viz., the earth is a vulnerable object in space that has, from time to time, undergone literal earthshaking events, most likely brought on by visitation of intense periods of comets coming near the earth and multiple asteroids or cometary fragments entering the earth’s atmosphere—pehaps coupled with anomalous solar activity—in the process setting off catastrophic geological upheaval including massive volcanoes and earthquakes, dramatically altering the earth’s climate and biological life.

Dobler had already had this realization and wrote about it, but having stopped short in my perusal of his book I had failed to get the full picture.

Ancient cometary impacts, the end of the dinosaur era and the end of the Wooly Mammoth

Dobler tells how the hypothesis introduced by Luis Alvarez and his son in 1980 that a comet impact in the Yucatan peninsula marked the end of the dinosaur era c. 65 million BC, while first met with ridicule, is now accepted by mainstream academia. How long will it take for academia to accept the evidence that the much more recent end of the era of large mammals c. 10,900 BC points to a similar cataclysmic event? Or of a “celestially induced catastrophe leading to the collapse of all the major Mesopotamian and Mediterranean empires” c. 1600 BC?

… [M]odern-day historians and archeologists are usually keen to attribute all events of abrupt Earth changes to either earthquakes or volcanoes, but not to cosmic impacts or cosmically induced electric events. In 1980, it took a long time for the scientific community to accept the reality of the Chicxulub impact(s) that ended the era of the dinosaurs c. 65 million years ago, and mainstream scientists will take even longer to accept the Younger Dryas Impact Event, 10,900 BC, although the evidence for this cosmic impact series has not been seriously challenged, by anything other than the cries of the usual Pavlovian academic outrage. The psychological processes responsible for this are rather complex, but yet so simple at the same time.

For one, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes happen regularly even in our recent, relatively quiet times, so that’s undeniable. Therefore, contemplations about whether the Santorini eruption in c.1600 BC. ended the Minoan era, are welcomed. But who dares to claim that the eruption itself was only one aspect of a global celestially induced catastrophe leading to the collapse of all the major Mesopotamian and Mediterranean empires, will be met with the said standard Pavlovian outrage of the academic establishment.

—p. 91

Discussing the Maars of the Eifel region of southern Germany dating to the beginning of the Younger Dryas cooling period, Dobler (p. 44-45) notes that,

The 10,900 BC eruption of the caldera that today contains ‘Lake Laach’ in the Eastern Eifel region was the largest volcanic eruption in Central Europe since the last Ice Age.

[…]

…researcher Dr. Wilhelm Pilgram presented compelling evidence that the Maars (or at least some of them) are in fact craters of impacts, which then triggered a new surge of volcanic activity. The Maars have no cone shaped volcano mounts, as almost all of the other confirmed extinct volcanoes in the Eifel region do.

Cataclysmic events between 2350 BC and 540 AD

The learned German professor and “father of historical pathology” J.F.C. Hecker had a similar realization of the cyclical nature of cataclysmic events, and their relationship to disease. In the opening to his 1832 book on the Black Death :

Nature is not satisfied with the ordinary alternations of life and death, and the destroying angel waves over man and beast his flaming sword.

These revolutions are performed in vast cycles, which the spirit of man, limited, as it is, to a narrow circle of perception, is unable to explore. They are, however, greater terrestrial events than any of those which proceed from the discord, the distress, or the passions of nations. By annihilations they awaken new life; and when the tumult above and below the earth is past, nature is renovated, and the mind awakens from torpor and depression to the consciousness of an intellectual existence.”

While the extinction events that led to the end of the dinosaurs c. 65 million years ago and to the end of the era of large mammals like the wooly mammoth and the sabertooth tiger nearly 13,000 years ago were extreme and abrupt in the greatest sense imaginable, other less extreme, yet still catastrophic global events happen at more frequent intervals—generally, it seems, every 700 to 900 years.

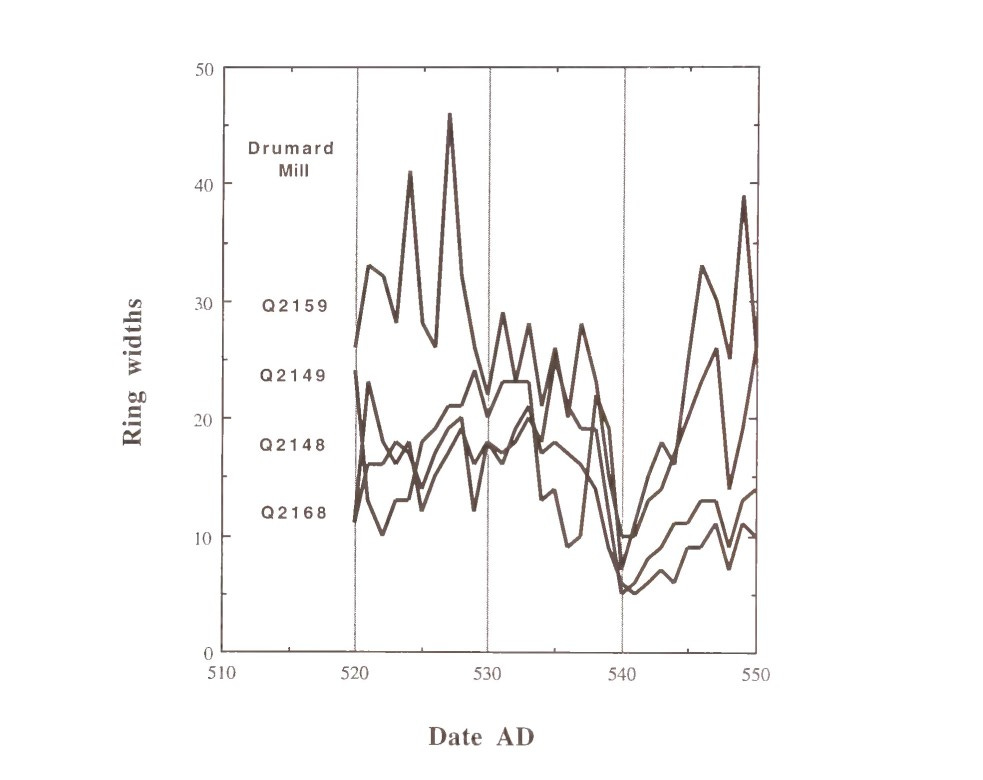

In his 1999 book, Exodus to Arthur: Catastrophic Encounters with Comets, Irish dendrochronologist Mike Baillie, professor emeritus in paleoarchaeology, notes 5 extreme climactic events visible in tree ring analysis between c. 2350 BC and c. 540 AD—the latter date corresponding to the Justinian Plague.

From a review of the book:

Baillie argues that the tree rings are recording first the Biblical flood, then the disasters that befell Egypt at the Exodus, famines at the end of King David’s reign, a famine in China that ended the Ch’in dynasty, and finally, the death of King Arthur and Merlin and the onset of the Dark Ages across the whole of what is now Britain.

The biblical account of Exodus and contemporary annals from China speak of cometary activity preceding calamity.

[…]

…Baillie goes a step further, arguing that a series of cometary impacts around the size of the 20-megaton explosion at Tunguska in Siberia in 1908 might be enough to trigger earthquakes, tidal waves, volcanic eruptions and ocean floor outgassing. This would explain why comets are seen as portent, along with the occurrence of flooding and poisonous fogs—all reported at the time of Exodus and during others of Baillie’s five catastrophes.

The 20-megaton Tunguska atmospheric explosion in 1908 flattened 1287 square kilometres of forest, felling 80 million trees; created an earthquake that registered 5 on the Richter scale, but left no crater

Notice Baillie’s suggestion of volcanoes and earthquakes being set off by “a series of cometary impacts.”

Supervolcanoes and global cooling

Baillie explains how large volcanic eruptions thrust debris miles high into the stratosphere from whence they become dispersed over the entire globe, causing dramatic global cooling and widespread climate disruption.

The essential thing about putting debris into the stratosphere is that it tends to stay up for quite a long time.

After a big explosive volcanic eruption the Earth is ‘veiled’ by a layer of fine debris made up of dust and tiny droplets of sulphuric acid, as well as ice crystals, circulating in the stratosphere. The overall effect of this ‘dust veil’ is to reflect away sunlight and cause the Earth’s surface to cool.

This in turn has a dramatic effect on tree growth, and is visible in where yearly growth rings become the narrowest. Tree ring analysis provides the most precise dating of extreme climactic event, and is supplemented with ice-core studies from Greenland and other places where layers of snow and ice have been built up over tens of thousands of years.

The graph above of ring width analysis of four ancient bog oaks from N. Ireland shows extremely narrow growth for 540AD in all four oaks. Local analysis like this one can be compared to other studies around the globe. (Reproduced from Exodus to Arthur by Mike Baillie)

Major climactic disruptions up to c. 540 AD as seen in tree ring analysis, corresponding historic events

2354 and 2345 BC - the Biblical flood (also in other traditions around the world)

1628 and 1623 BC - Santorini eruption; end of the Minoan era; biblical plagues of Egypt

1159 and 1141 BC - famine at the end of King David’s reign(?)

208 and 204 BC - end of the Ch’in dynasy

AD 536 and 545 - sun darkened for 18 mos. from the Mediterranean to China; extreme flooding in Peru and Chile; Mayan “dark age” begins; death of Arthur and Merlin; the Justinian Plague

Diverse traditions tell of widespread destruction and renewal

Hopi and Maya traditions tell of 5 worlds. Three have gone before, each being destroyed by great cataclysm. I never could quite understand, or believe what they were telling was true. I knew there had been a universal flood and this must have had something to do with their cosmology. Now it all begins to make perfect sense. There has been not one, but repeated times of great destruction and remaking of the world.1 Their stories are real, born out of the deep the memory of their people. We are now in the 4th world, they tell us, and according to Hopi prophecy we have another time of great calamity, earthquakes and floods to endure, another purification and renewal of the Earth before we enter the fifth—a new era, this time an era of harmony unlike the past, the Hopi tell us.

This cyclical nature of destruction and renewal of the earth is spoken of in cultural traditions scattered across the globe. Plato’s Timaeus recounts how after learned Greek lawmaker Solon gave an account of the history of his people to a group of Egyptian priests, one of them stepped forward and said:

O Solon, Solon, you Hellenes are never anything but children, and there is not an old man among you.

When Solon asked what he meant, the priest explained that the Hellenes were young in mind; their histories could not relate what happened in very ancient times because whenever there was a great deluge water would come down from the mountains and destroy their cities. Only shepherds and unlettered people would be left. Having lost the records of their history, they would begin again as children. But in Egypt, in the plain of the Nile, floods would always come up from below. Their civilization was not utterly destroyed and the records of the past were still safeguarded in their temples. While the Hellenes knew of only one Great Deluge, the priest assured him, there had in fact been many, along with destructions by fire (perhaps a reference to meteor explosions, volcanoes or severe electrical storms).

There have been, and will be again, many destructions of mankind arising out of many causes…

The fact is, that … the human race is always increasing at times, and at other times diminishing in numbers. And whatever happened either in your country or in ours, or in any other region of which we are informed (…) all that has been written down of old, and is preserved in our temples (…)

—Egyptian priests to the Greek lawmaker Solon as told by Plato in Timaeus

By contrast, the periods of the Justinian Plague and the Black Death are relatively recent and are still well within our cultural memory. Yet there is a willful ignorance, and even suppression, of the historical record. For whenever these plagues are talked about, nary a mention is made of concurrent catastrophic upheaval of the earth, despite abundant historical and even contemporary accounts still extant. It is as if these plagues arose from nowhere—spontaneous events exclusively attributed to a horrifying, dangerously-spreading bacterium. Nothing else worth mentioning happened to caused them.

I’m here to set that record straight.

13th and 14th Century Events and the Black Death

“In France. . . was seen the terrible Comet called Negra [1347]. In December appeared over Avignon a Pillar of Fire. There were many great Earthquakes, Tempests, Thunders and Lightnings, and thousands of People were swallowed up; the Courses of Rivers were stopt; some Chasms of the Earth sent forth Blood. Terrible Showers of Hail, each stone weighing 1 Pound to 8; Abortions in all Countries; in Germany it rained Blood; in France Blood gushed out of Graves of the Dead, and stained the Rivers crimson; Comets, meteors, Fire-beams, coruscations in the Air, Mock-suns, the Heavens on Fire.”

— A General Chronological History Of The Air, Weather, Seasons, Meteors, & Comets (1749) by Thomas Short

In the opening to his book, Dobler gives a summary of events beginning in the early 1300s—extreme events including “natural disasters that led to crop failure, abandonment of farm land, and the Great Famine that killed about 30% of the European population” that had already taken a heavy toll decades before the onset of the Black Death. Immediately preceding the years of the Black Death, weather was so bad that chroniclers across Europe recorded “four years without summer.” On January 25, 1348, just weeks before plague broke out in central Europe, an extensive earthquake destroyed the town of Villach in the Austrian Alps and inflicted heavy damage on churches and other structures as far away as Rome. In fact, multiple earthquakes were reported both before and after that fateful year.

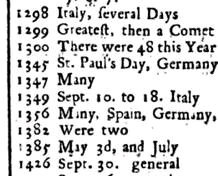

A list of earthquakes from Thomas Short’s General Chronology (1749) shows four entries between 1345 and 1356, around the time of the Black Death in Europe. He omits the Great Fruili quake (or quake swarm) of 1348.

It was the same month of January 1348 that plague first visited Avignon in southeastern France, where a “pillar of fire” had been seen over the Pope’s palace in December of the previous year.

Dobler summarizes the situation as follows:

The period from 1310-1350 saw the death of at least 50 to 70% of the population of Europe and Asia, in some areas, the accumulated death toll of the years of the Black Death alone is believed to be in the 75% range. It took more than 200 years for the population of Europe to recover to the previous numbers of the late 13th century. Already in 1315 -1320, the decline in population coincided with natural disasters that led to crop failure, abandonment of farm land, and the Great Famine that killed about 30% of the European population.

The greatest loss of life is of course attributed to the Black Death pandemic of 1348-51, which is commonly believed to be the result of a contagious disease imported from the far East.

Traditional models contend it to be bubonic plague, others suggest pneumonic plague, anthrax or small pox.

The period from 1290 onward saw severe climate change and astronomical anomalies, which culminated in the 1348 crisis. The events at this climax involved comet/meteor sightings, earthquakes, noxious gases from the air, from the ground and the sea.

[…]

Even at the time of the Black Death pandemic, a range of various possible causes were proposed, almost all of them were based on the perception of poisons, foul odors and ‘contaminated winds’ coming from the sky, from the ground and from the sea. These were said to be directly related to earthquakes and/ or meteors. The observation of “foul” drinking water supplies is most likely what led to the idea that ‘someone’ had poisoned the wells, which would only have been possible in some cities, considering the poisons available at the time. The Jews were accused of having done so, and executed in large numbers after confessions were extorted under torture.

In the early years of the pandemic, few seemed to have been concerned with person to person transmission of the disease, although there is an abundance of reports of people abandoning their sick loved ones. But this was apparently not because they were afraid of direct physical contagion. The idea of quarantine was introduced only at a later stage of the pandemic. However, Doctors did advise to stay away from corpses and to refrain from eating fish.

– Black Death and Abrupt Earth Changes in the Fourteenth Century (2018), by Sasha Dobler

The Wolf Solar Minimum, volcanoes & comets

Dobler believes the events of this period are explained by not just comet/meteor activity but by changes in the sun’s activity. Dramatic climate cooling coincided with the Wolf Solar Minimum (roughly 1280-1350 AD) [Dobler 5.1.6]. Even by the mid 13th century, sunspot count would reach sporadic lows. Dobler cites researchers Toshikazu E. et al. (2011) on the correlation of the above with volcanoes:

“[L]ow sunspot counts and thus more cosmic ray influx are directly correlated to volcanic eruptions.”

Heavy 13th century volcanic activity—revealed by ice core analysis—brought an end to the warm Medieval Climate Optimum. By the beginning of the 14th century, climate disruption in Europe was already severe.

As it turns out, the first climate downturn that initiated the Little Ice Age, was preceded by excessive amounts of sulfate injections into the atmosphere, which is attributed to volcanoes. A study by Gao et al of 2008 connects temperature, volcanic activity, sulfate emission and solar activity, as they investigated one of the most important natural causes of climate change, volcanic eruptions.

[…]

“The largest volcanic perturbation is measured at 1259.”

The year 1259, in fact, records what was probably the largest release of volcanic debris into the atmosphere in centuries. Thus the 13th century had already set the stage for dramatic climate cooling and disruption as debris from more volcanoes continued to accumulate in the upper atmosphere.

Solar activity has been correlated not only with volcanoes but with earthquakes, and becomes erratic in the presence of comets.

A solar flare reaches out toward a comet.

One begins wondering just how and in what ways all of these things are connected and how they interrelate.

“Clube and Napier note the mid 14th century as a period of high meteoritic activity.” says Dobler [Napier, B, Clube, V. 1990; The Cosmic Winter; Oxford p. 43]. As likely occurred at the time of the Tunguska event, heavy meteor showers can be the result of debris from comets.

Dobler distinguishes between the decades of climate disruption and catastrophe in the first half of the 14th century and the increased intensity of events of the period of the Black Death between 1348 and 1353.

In the former we notice minor meteor events, aurorae, worsening of weather. During the later we find a sudden culmination of these occurrences, and in particular an increase in reported meteor and comet sightings. For this the only feasible explanation from what we know today, is the crossing of a denser part of a meteor stream that contains larger objects. The great mystery remains how this was announced in the form of long term changes that involved the sun itself.

—Dobler, p. 52

One is reminded of Hecker’s sober words:

To attempt, five centuries after that age of desolation, to point out the causes of a cosmical commotion … which called forth so terrific a poison in the bodies of men and animals, exceeds the limits of human understanding.

Baillie’s “New Light on the Black Death”

Professor Baillie dedicated decades of his life to the analysis of Irish oak tree rings. His team constructed a 7000 year record using thousands of Irish oaks. This record can be compared to other tree ring analyses in countries like Germany and the United States. It can also be compared with ice core data from Greenland and Antarctica or alpine glaciers.

When Bailey compared very narrow ring growth during the years of the Black Death to Greenland icecore data, he found something very strange: ammonium.

Jadczyk’s review of his 2007 book, New Light on the Black Death tells the story:

There are, as it happens, four occasions in the last 1500 years where scientists can confidently link dated layers of ammonium in Greenland ice to high-energy atmospheric interactions with objects coming from space: 539, 626, 1014, and 1908 - the Tunguska event. In short, there is a connection between ammonium in the ice cores and extra-terrestrial bombardment of the surface of the earth.

Now notice that the above statement is that there are four events that can be definitively [emphasis added] linked with high-energy interactions; Baillie presents the research in this book showing that the exact same signature is present at the time of the Black Death in both the tree rings and in the ice cores, AND at other times of so-called "plague and pandemic".

As it happens, the ammonium signal in the ice-cores is directly connected to an earthquake that occurred on January 25th, 1348 - and Baillie discovers that there was a 14th century writer who wrote that the plague was a "corruption of the atmosphere" that came from this earthquake! [actually, more than one writer pointed to this]

How could a plague come from an earthquake, you ask?

(The author goes on to conjecture about cometary explosions, but I would like to point out at the outset that earthquakes themselves can release poisonous gasses trapped beneath the earth, and it seems that this is what contemporary reports suggest.)

Baillie points out that we don't always know if earthquakes are caused by tectonic movements; they could be caused by cometary explosions in the atmosphere or even impacts on the surface of the earth.

In Rain of Iron and Ice by John Lewis, Professor of Planetary Sciences … tells us that the earth is regularly hit by extraterrestrial objects and many of the impacting bodies explode in the atmosphere as happened in Tunguska, leaving no craters or long-lasting visible evidence of a body from space.

But just because there is no long-lasting evidence doesn't mean there is no significant effect on the planet and/or its inhabitants![…]

The point of this is that there is almost no way to monitor whether or not any given disaster/catastrophe is definitively an impact as opposed to a violent earthquake. The result is that centuries could be passing, with numerous cometary impacts happening all the time, and no one suspecting the true hazards from space! As Baillie points out: there are many earthquakes recorded in history, but NO impacts! And yet, there is the evidence that the impacts HAVE happened - on the ground, and in the ice cores. And there is Tunguska.

Reports of the Tunguska event tell us that the ground shook around the impact/explosion zone for a radius of about 900km. At the time of any larger impact event, the earthquake would be proportionally more severe. Any survivors of such an event who are far enough away to survive, would only have seen a flash, felt a tremor, and heard a loud rumbling noise. If they were too far away to see the flash, or were indoors, they would only report an earthquake.

In short, what the work of Lewis brings to the table is the idea that some well-known historical earthquakes could very well have been impact events. Baillie mentions that one obvious prospect is the great Antioch earthquake of AD 526 which was described by John Malalas:...those caught in the earth beneath the buildings were incinerated and sparks of fire appeared out of the air and burned everyone they struck like lightning. The surface of the earth boiled and foundations of buildings were struck by thunderbolts thrown up by the earthquakes and were burned to ashes by fire... it was a tremendous and incredible marvel with fire belching out rain, rain falling from tremendous furnaces, flames dissolving into showers ... as a result Antioch became desolate ... in this terror up to 250,000 people perished…. The Chronicle of John Malalas

Curiously, prior to a 2016 earthquake in Ecuador, a “fireball” was seen in the sky. Could it have been a meteor or comet?

Whether or not either the 526 AD “earthquake” or the January 25, 1348 event can be concluded to have been the result of impacts from space, the association of the latter with the advent of plague in the same region is clear. This will be discussed later in detail. But first let’s take a look at the great turmoil in China and other places in the world in the first half of the 14th century.

Hecker’s account of natural disasters in China

Hecker chronicles extreme geological and climactic upheaval beginning in China in the year 1333. His account (see Appendix), is summarized in the first chapter of a modern, elegantly narrated volume, The Great Mortality:

In the 1330s there were reports of tremendous environmental upheaval in China. Canton and Houkouang were said to have been lashed by cycles of torrential rain and parching drought, and in Honan mile-long swarms of locusts were reported to have blacked out the sun. Legend also has it that in this period, the earth under China gave way and whole villages disappeared into fissures and cracks in the ground. An earthquake is reported to have swallowed part of a city, Kingsai, then a mountain, Tsincheou, and in the mountains of Ki-ming-chan, to have torn open a hole large enough to create a new "lake a hundred leagues long." In Tche, it was said that 5 million people were killed in the upheavals. On the coast of the South China Sea, the ominous rumble of "subterranean thunder" was heard ...

The author cited above does not attempt to modernize Hecker’s 1832 place names, which do not correspond to today’s.2

Hecker first mentions plague as following a severe drought in Tche in the year 1334—five million died. More geological upheavals and more droughts, floods and pestilence followed. (See Timeline and Appendix)

But in the year 1347, “the fury of the elements subsided in China,” Hecker writes.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the world similar events were seen.

Climate disruption and floods in South America & India

In a section on the Americas [7.1.1], Dobler shows how climate patterns in South America matched those in Europe.

An Argentinian study of … the Andes of northern Patagonia found comparable patterns of climate change as are known from Europe … :

“Four main climatic episodes can be distinguished in this proxy paleoclimatic record. The first, a cold and moist interval from A.D. 900 to 1070, was followed by a warm-dry period from A.D. 1080 to 1250 correlative with the Medieval warm epoch of Europe. Afterwards, a long, cold-moist period followed from A.D. 1270 to 1670, peaking around A.D. 1340 and 1650.”

(Note the period from 1270 to 1670 is generally referred to as the Little Ice Age. Warming began in the following centuries and continues to today.)

Further, under the subheading Miraflores flood, Dobler cites two studies on extreme flooding that “forced the decline of the Chiribaya culture ca. A.D. 1330 on the coasts of Chile and Peru.”

In India, “In the year 1341” Dobler writes (p. 20):

… the great flood in the river Periyar in modern-day southern India led to the river changing its course, closing off Muziris, opening up Cochin (Kochi) harbor, it submerged some islands and gave birth to some new islands.

Millenial Floods in Europe 1342-1343

Hecker writes,

…great floods occurred in the vicinity of the Rhine and in France, which could not be attributed to rain alone ; for everywhere, even on the tops of mountains, springs were seen to burst forth, and dry tracts were laid under water in an inexplicable manner.

France was not alone. Dobler (3.1.2) reports that many countries in Europe saw floods in the years 1342-1343, of the kind not seen in a thousand (or many thousands) of years. Germany was the most severely affected. Multiple, millennial floods were caused by not only diluvial rains but by sea surges as well. Dobler cites a paper by the Austrian Technological University on the subject:

[W]e would like to draw the attention to the extraordinary character of the entire year of 1342, and also of 1343 … providing an overview of the flood and sea surge events and flood waves that occurred during these two extraordinary years in Europe …

… at least 3 (but maybe even 4) flood waves occurred which were of millennial level, and repeated extreme floods occurred especially in Central Europe, but parts of West-Europe as well as the North Mediterranean were also badly hit by extreme floods or sea surges in these two years

Read Dobler’s 3.1.2 Magdalene Flood 1342-43 for more astonishing details of these floods.

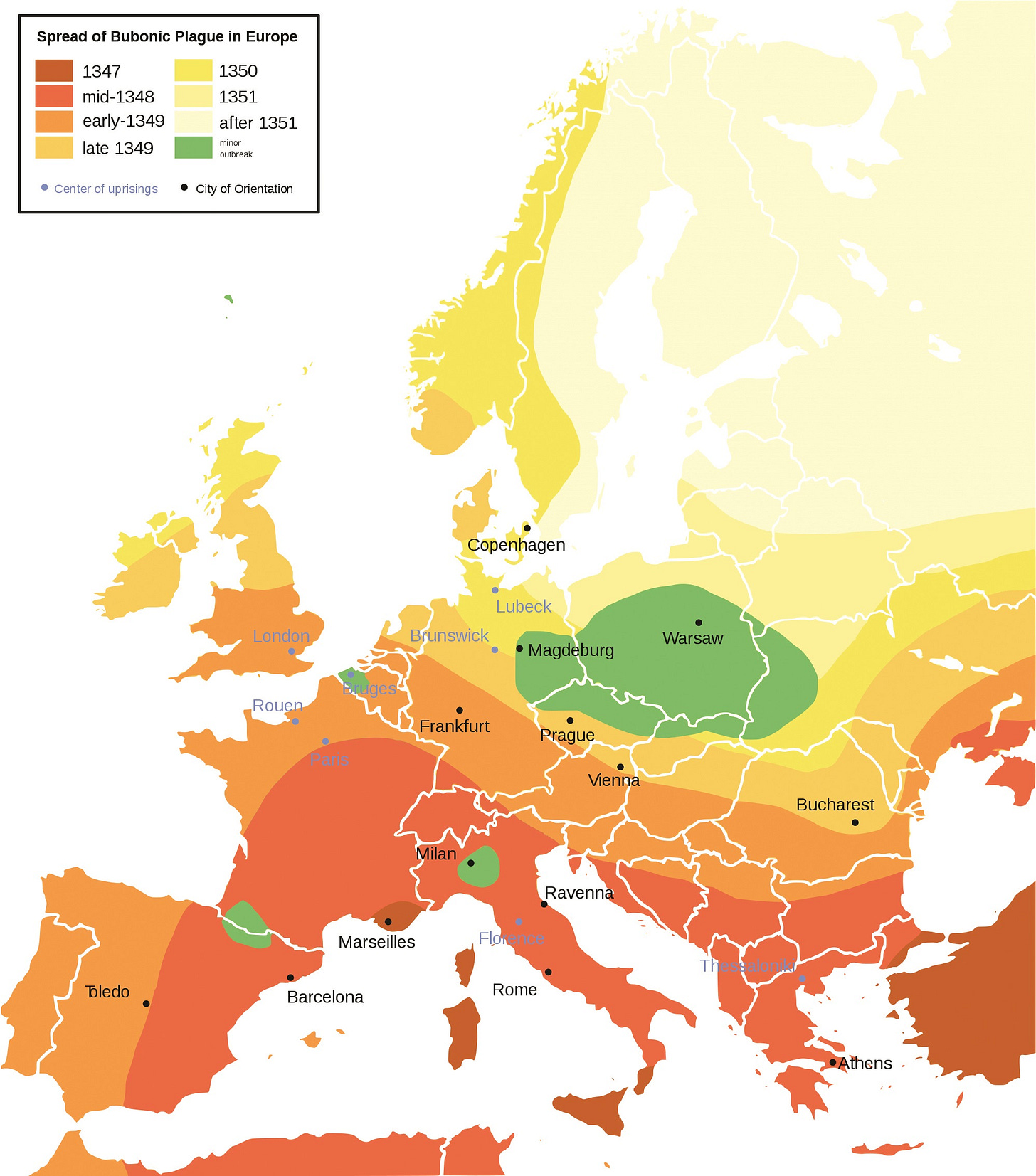

How did the Black Plague spread in Europe?

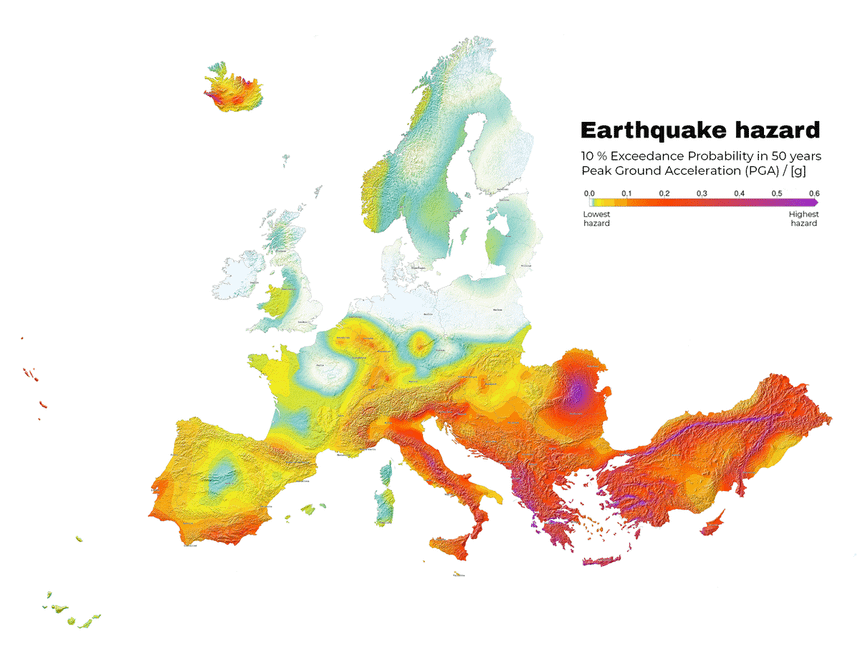

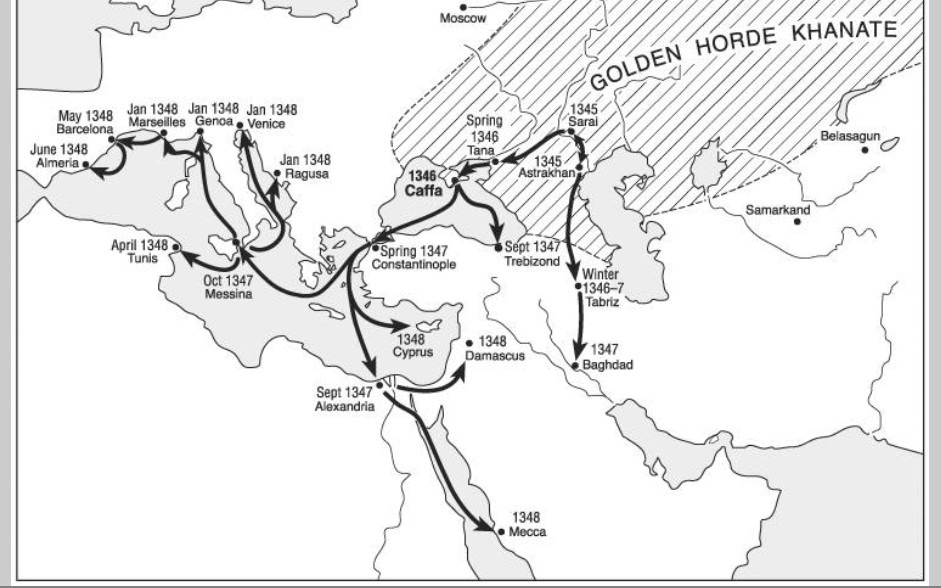

The plague is assumed to have arrived first in the Mediterranean from the north and east, from the hinterlands past the Black Sea designated the Golden Horde, or the Turkish “Great State.” The following modern day map of earthquake hazard in Europe shows probability of geological disturbance in these areas:

This can be compared to maps of the spread of plague (see below), though it should be made clear that these maps show the year of spread rather than mortality. The suggestion here is not that the black death did not occur in northern countries but arrived there late and followed a round about route, if we are to believe it that it came from the east.

14th Century Biological Warfare?

The last of these maps—the one immediately above—is taken from a research article examining Gabriel de Mousi’s 14th century account alleging that during a seige of the bustling Genoese trading outpost of Caffa (Kaffa) on the northeastern shore of the Black Sea the Mongolian army catapulted “mountains of dead” bodies of plague victims into the city, thus not only sickening its inhabitants with the stench and poisoning their water but leading to the spread of the plague throughout Europe by means of Genoese galleys fleeing the city.

De Mousi was a notary in Piacenza, north of Genoa on the Italian peninsula, and the earliest copies of the account are from around 1367. Though by all measures de Mousi’s tale does not appear to be a firsthand account and though it is uncorroborated, the research article’s author believes the spread of the plague to the city via catapulted bodies to be plausible. On the other hand, he thinks the event is unlikely to have been the source of spread to Europe given that if this were the case then the spread should have been seen within only a few months.

Plague appears to have been spread in a stepwise fashion, on many ships rather than on a few (Figure 1), taking over a year to reach Europe from the Crimea. This conclusion seems fairly firm, as the dates for the arrival of plague in Constantinople and more westerly cities are reasonably certain. Thus de’ Mussi was probably mistaken in attributing the Black Death to fleeing survivors of Caffa, who should not have needed more than a few months to return to Italy.

Thus we are left with a possible though uncorroborated account of morbid warfare, but what is remarkable here is a slow, allegedly stepwise spread westward, as seen in the maps above. One might also note that pestilence is given by Hecker to have already taken heavy tolls in China more than a decade earlier, although the nature of that pestilence seems uncertain.3 If it was plague caused by a bacterium and infected rodents, why did it not spread early to the Black Sea along the Silk Road, where caravans had not ceased to travel?

The official story told today is that Genoese ships coming from Kaffa brought the Black Plague to Italian ports. Specifically, twelve galleys, dubbed “death ships” coming from “the east” are said to have landed in October at the port of Messina, Sicily, with dead or dying passengers aboard. I’ve been unable to identify any original sources for this story. Perhaps noteworthy, however, is that the port is located along the Messina Strait just north of Mt. Etna, where weak strombolian activity appears to have been going on since March of that year, including pyroclastic flows of hot gasses.4

The Great Fruili Earthquake of Jan. 25, 1348

Centered in the South Alpine region of Friuli, the quake was felt across almost all of Europe. The quake hit in the same year that the plague situation escalated in Italy, the outbreak followed only months later. About 200 contemporary sources mention this event. It caused considerable damage to structures; churches and houses collapsed, villages were destroyed. Interestingly, witnesses also reported that foul odors emanated from the earth.

It was a rather extraordinary type of earthquake, with a wide spread impact region, causing structural damage throughout Upper Italy and Austria, and caused minor damage as far away as Naples, throughout all of Bavaria, Bohemia, Hungary and today’s Slovenia. In Carinthia, the town of Villach and numerous surrounding villages were largely destroyed by a major landslide followed by a flood of the Gail River. Even as far away as Rome, the earthquake allegedly took its toll…

Now, if we combine the affected regions, we find the quake’s impact range adds up to about 1400 km

—Dobler, p. 29

First hand reports of the quake point to sustained aftershocks over the following weeks. Dobler suggests that because of its broad geographical extent this may have been what he calls earthquake “swarm” rather than a single quake. Given the widespread reports of poisonous vapors emanating from the earth, it seems that vents may have been opened up in various places, possibly including under the sea.

If the reader doubts that poisonous gasses can be trapped beneath the earth, one only needs to be reminded that miners must be vigil of poisonous gasses, thus the traditional use of canaries to warn of danger: if the canary keels over, IT’S TIME TO GET OUT!

This very fact of poisonous fumes in mines is mentioned in Konrad von Megenberg‘s 1349 Book of Nature, in a section describing earthquakes and the Black Death (translated by Dobler, p. 100):

This also happens with minors [sic], that they become dizzy and sway like drunkards when they descend into the mine, and this even though the vapour wasn’t trapped long in one spot, for the shafts were open.

Immediately after saying this, Megenberg goes on to describe the quake that began “on the day of Paul’s Conversion”—i.e. St. Paul’s day, January 25, 1348—which he says “continued over 40 days, after the initial shock, there were many smaller tremors for days and weeks.” (He notes another earthquake on St. Stephen’s Day in the same mountain range the following year.)

Keep in mind, that the vapour had accumulated, as it was trapped inside the mountains! As it now broke out into the air, it was natural that it poisoned everything on the other side of the mountains over hundreds of miles, and also on this side of the mountains to a great extent. It became clear early, that in the same and also in the following years, there would be the greatest mortality since the time after and possibly even before Christ…

In the cities on the coast, as in Venice, Marseille, throughout Apulia and at Avignon, endless numbers of people died. In the first year of the great earthquake, the grief was so great, that pope Clemens the sixth ordered a new mass for the death, to implore God to have pity on the people. The mass began with the words: Recordare Domine testamenti tui!

This last may be plea for God to remember his promise not to destroy the earth again by a flood!

Megenberg continues:

Many things indicated that the general mortality came from the poisoned air.

The first is, that the mortality began first and foremost in the mountains and in coastal cities, for there, the mists were the densest and the most poisonous. Because [the seas trapped the] the air in the Earth’s veins near [them] … thus also the waters were poisonous.

The [second] thing is that the majority of the ill people that died, had ulcers under the armpits… That was because the person had absorbed the evil air, and this remained in the flesh of the chest around the heart. … [T]he heart was damaged by it and the person … suffocated. That is why mostly young people of tender nature died, and first and foremost young women.

The third sign is, that the deadly mortality in the years after the earthquake, caused only little harm to the people that were in the vicinity of the mountains in the high places. As the heavy poisoned air was lifted from the mountains and descended soon to the earth, the higher air remained purer than the lower air.

The fourth sign is, that in autumn and winter of the two years, many dense and very scorched smelling vapors were prevalent, because the earthly vapours in the air were transformed into mists and it was so dense that it descended to the earth. It was particularly dangerous for people who inhaled the mist in the morning before eating or drinking. Therefore, careful people remained in the dwellings in the morning, fumigated their rooms with pleasantly smelling and precious things and they ate early, before the harmful air could enter their empty bodies.

[…]

…some claimed that the plague came from a certain star, and as long it was visible the mortality would continue.

Hecker also gives an account of “poisonous odors” associated with an earthquake in Cyprus. He doesn’t give a date, but it seems he must have been referring to early 1348 or late 1347.

“On the island of Cyprus, the plague from the East had already broken out; when an earthquake shook the foundations of the island, and was accompanied by so frightful a hurricane, that the inhabitants had slain their Mahometan slaves, in order that they might not themselves be subjugated by them, they fled in dismay, in all directions. The sea overflowed- the ships were dashed to pieces on the rocks, and few outlived the terrific event, whereby this fertile and blooming island was converted into a desert. Before the earthquake, a pestiferous wind spread so poisonous an odor, that many, being overpowered by it, fell down suddenly and expired in dreadful agonies.”

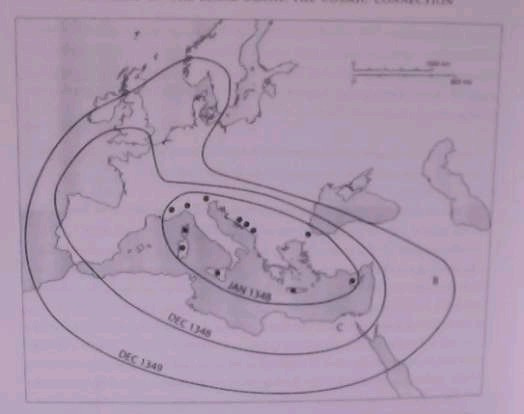

Baillie’s Map of Spread

Below is a map constructed by Mike Baillie assuming that Jan. 1348 (as opposed to late 1347) was the real start of the Black Death in Europe. It shows concentric rings of spread starting in the north Mediterranean.

Dobler says this map is accurate and time-corrected, affirming that, “The real distribution pattern of the spread of the plague is more consistent with harmful substances being emitted from the sea, or clouds of gases being blown in from the Eastern Mediterranean Sea,” says Dobler.

Map of spread of the Great Pestilence (later dubbed Black Death). Dates beginning with inner circle: Jan. 1348, Dec. 1348, Dec 1349. Black dots mostly from Peter Rasmussen’s list of definite first occurrences. Graphic: Mike Baillie 2006

Symptoms of the Black Death in Europe

Insofar as the mortality arose from natural causes its immediate cause was a corrupt and poisonous earthy exhalation, which infected the air in various parts of the world... I say it was the vapour and corrupted air which has been vented - or so to speak purged - in the earthquake that occurred on St. Paul's day [January 25, 1348], along with the corrupted air vented in other earthquakes and eruptions, which has infected the air above the earth and killed people in various parts of the world.

--An early German account of the Black Death (cited by Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death)

According to modern mythology, the Black Death was an epidemic of bubonic plague. Modern medicine subdivides plague into two main categories, although other categories exist.

“Bubonic” plague refers to enlarged lymph nodes, called buboes, in the groin or under the armpits. Note that this symptom in itself is not exclusive to “plague” but occurs in many other conditions.

Pneumonic plague refers to a species of disease affecting the lungs. While both are claimed to be caused by y. pestis bacteria, modern plague epidemics are generally said to be one or the other and pneumonic plague is said to be rarer and more acute and fatal, which in itself begs the question of how a single bacterium, or even strains thereof, can produce such distinct afflictions.

From what I can gather, however, the sickness of the Black Death period could not be said to be one or the other of these two forms, but rather it appears to be that upon first reaching a population center, severe onset of respiratory symptoms led to very quick death, whereas only later, in those not killed in the respiratory assault, large black or blue spots, blisters or even stripes covering the entire body might develop and, additionally, in only some cases perhaps, lumps might be seen in the groin area or armpits.

J.F.C. Hecker, a learned German physician gives a description of the symptoms in the opening pages of his book, Black Death (1832), p.3-4.

Still deeper sufferings, however, were connected with this pestilence, such as have not been felt at other times ; the organs of respiration were seized with a putrid inflammation ; a violent pain in the chest attacked the patient ; blood was expectorated, and the breath diffused a pestiferous odour.

In the West, the following were the predominating symptoms on the eruption of this disease. An ardent fever, accompanied by an evacuation of blood, proved fatal in the first three days. It appears that buboes and inflammatory boils did not at first come out at all, but that the disease, in the form of carbuncular (anthraxartigen) affection of the lungs, effected the destruction of life before the other symptoms were developed.

Dobler (p. 65) expands on this in his discussion of how the modern reductionist portrayal of the Black Death conflict with earlier reports:

Contemporary writers gave very different descriptions of symptoms and modern day editors had a lot of work to do in order to arrive at a consensus of what the victims suffered from. If I would have to give a condensed summery, I would say: Nobody really knows!

Hecker maintains that the characteristic buboes that are confined to the groin and armpits don’t appear in the primary sources written by doctors at the time:

“Only two medical descriptions of the malady have reached us, the one by the brave Guy de Chauliac, the other by Raymond Chalin de Vinario, a very experienced scholar, who was well versed in the learning of the time. The former takes notice only of fatal coughing of blood; the latter, besides this, notices epistaxis [i.e. nosebleed, seen often in epidemics of hemoragic fever], hematuria [blood in the urine], and fluxes of blood from the bowels, as symptoms of such decided and speedy mortality, that those patients in whom they were observed usually died on the same or the following day.”

… I find only one contemporary source, Konrad von Megenberg, that can be reliably be considered unaltered, who explicitly describes buboes in the armpits (see page 100).

And then Hecker directly addresses atmospheric poisons involved:

“Now, if we go back to the symptoms of the disease, the ardent inflammation of the lungs points out, that the organs of respiration yielded to the attack of an atmospheric poison− a poison which, if we admit the independent origin of the Black Plague at any one place of the globe, which, under such extraordinary circumstances, it would be difficult to doubt, attacked the course of the circulation in as hostile a manner as that which produces inflammation of the spleen, and other animal contagions [i.e. poisons] that cause swelling and inflammation of the lymphatic glands.”

[…]

There is no safe way to confirm what percentage of the afflicted did actually have any buboes at all. Most sources speak of non-discriminate, ‘boils; furuncles, cysts’ distributed over the body, and/or black/blue spots all over the body. Not all of them even mention the outward effect on the skin.

As a side note, black/blue spots would today likely be diagnosed as Kaposi Sarcoma which is believed to be [caused by] HIV, but can be a simple result of chronic amyl nitrate poisoning (amyl nitrate[s] are the main ingredients of the party drug poppers).

Any nitrites enhance neutrophil-induced DNA strand breakage in pulmonary epithelial [tissue?]. Organic compounds similar to amyl nitrate can be created in high velocity impacts [note: the term “impact” is frequently used to describe atmospheric explosions that leave no craters]. Similar hydrocarbons are contained in comet tails, for instance CO, (carbon monoxide), and CN (cyanogen) are common in comet tails.

An early report (see Dobler, p. 65) says similarly:

The disease is threefold in its infection; that is to say, firstly, men suffer in their lungs and breathing, and whoever have these corrupted, or even slightly attacked, cannot by any means escape nor live beyond two days. Examinations have been made by doctors in many cities of Italy, and also in Avignon, by order of the Pope, in order to discover the origin of this disease. Many dead bodies have been thus opened and dissected, and it is found that all who have died thus suddenly have had their lungs infected and have spat blood.”

The predominance of rapid onset of extreme acute respiratory distress and the coughing of blood would make sense in the context of a creeping, foul-smelling fog laden with poisons released during widespread upheaval of the earth’s crust and/or from meteor/cometary impacts.

Problems with the Y. Pestis hypothesis

During a severe pneumonic (i.e. respiratory) plague outbreak in Hong Kong in 1894, the discovery was made of the bacterium yersinis pestis, credited to Alexandre Yersinis, a student of both Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur. The bacterium, isolated from the blood of plague victims, was promptly blamed for causing not only pneumonic plague but bubonic plague as well and, since the Black Death was asserted to be bubonic plague, the bacteria became the scapegoat. This, more than five centuries after the fact!

The officially accepted hypothesis about the Black Death is that Y. Pestis was the culprit and was spread by flea-infested rats. However, this hypothesis is not without its problems.

“At its most basic, the problem is with those rats and fleas,” Baillie says in his 2007 book New Light on the Black Death.

For the conventional wisdom to work there have to be hosts of infected rats and they have to be moving at alarming speed - you would almost have to imagine infected rats scuttling ever onward (mostly northward) delivering, as they died, loads of infected fleas. The snags with this scenario are legion. For example, there are no descriptions of dead rats lying everywhere (this is explained by suggesting that either the rats were indoors, or people were so used to dead rats that they were not worth mentioning; though if they were indoors how did they travel so fast?) It did not seem to matter whether you were a rural shepherd or cleric or a town dweller, both were infected. Yet strangely with this very infectious disease some cities across Europe were spared. Moreover, these rats must have been happy to move to cool northern areas even though bubonic plague is a disease that requires relatively warm temperatures. Then, when there are water barriers, these rats board ships to keep the momentum going.

—Baillie, quoted in Laura Knight-Jadczyk’s review of his 2007 book, New Light on the Black Death

The problems with Y. Pestis officialdom are so obvious that a number of other culprits have been proposed, including anthrax, smallpox and even ebola, with entire books dedicated to the subject.

Jakczyk goes on:

In 1984, Graham Twigg published The Black Death: A Biological Reappraisal, where he argued that the climate and ecology of Europe and particularly England made it nearly impossible for rats and fleas to have transmitted bubonic plague and that it would have been nearly impossible for Yersinia pestis to have been the causative agent of the plague, let alone its explosive spread across Europe during the 14th century. Twigg also demolishes the common theory of entirely pneumonic spread. He proposes, based on his examination of the evidence and symptoms, that the Black Death may actually have been an epidemic of pulmonary anthrax caused by Bacillus anthracis.

Another unhappy camper in the standard model is Gunnar Karlsson who, in 2000, pointed out that the Black Death killed between half and two-thirds of the population of Iceland, although there were no rats in Iceland at this time. (The History of Iceland by Gunnar Karlsson)

In fact, so varied and complex the problem becomes that one article on the NIH website says we can’t be sure the Black Death had a single microbial cause.

Most medievalists, including those who doubt that the Black Death and subsequent plagues could have been caused by Yersinia pestis, make a modern assumption that the Black Death indeed had some unique microbial cause. No one yet has argued in a sustained fashion that the plague was a “perfect storm” of many different epidemic infectious diseases, but one could.2 Nor has a radical scepticism emerged—for example, that the causes of each and every local or regional epidemic called peste/pestilentia by contemporaries need to be investigated separately, unrelated to other local contexts—but that, too, might be possible. If we would be truly rigorous, we cannot assume that a “plague” in one place was due to the same specific microbial cause as a pestilence in another locality, even during this worst of all recorded pandemics. There needs to be evidence for such a claim.

If this be the case, then how can we be sure the cause was “microbial” at all, given that firsthand reports and geological evidence point to much more phenomenal atmospheric and geological events already described? And only this can make sense of a level of mortality that makes WWII look like Mom’s apple pie.

Testing skeletal remains

Some will still claim that skeletal remains from 14th century plague graves have “proven” it was y. pestis, ignoring the counterevidence. Resuming with the book review cited above:

When one begins to dig into the subject, we find that there was one study that claimed that tooth pulp tissue from a fourteenth-century plague cemetery in Montpellier tested positive for molecules associated with Y. pestis (bubonic plague). Similar findings were reported in a 2007 study, but other studies have not supported these results. In fact, in September of 2003, a team of researchers from Oxford University tested 121 teeth from sixty-six skeletons found in fourteenth-century mass graves. The remains showed no genetic trace of Y. pestis, and the researchers suspect that the Montpellier study was flawed.

What these studies do not address is the problem that the apparent means of infection or transmission varied widely…

It should be stressed that when archeologists claim to have detected what they believe to be DNA belonging to certain bacteria or “viruses” in skeletal remains, this is not proof of causation. Contrary to what the populace has been led to believe, “deadly” bacteria are found practically everywhere, and can be found in the healthy as well as the sick. The term “asymptomatic carrier” was invented long ago so that the “scientific” establishment could continue to claim certain bacteria to be pathogenic, even when in a majority of cases no illness appears in association with them. Moreover, it has been debated since the days of Pasteur whether the appearance of certain bacteria in diseased tissue are the cause or result of the illness.5

(See the Introduction to Part 1 on the alleged contagiousness of plague.)

“Plague”, a non-specific ailment

Given all of the above, it appears that what we are dealing with during the period under discussion is many different manifestations of disease varying with time and place and brought on by local conditions, which predominately included corruption of the atmosphere, famine, wars, etc. In other words, “plague” would appear to be a catch-all term embracing a wide variety of afflictions leading to death. This is confirmed by the NIH webste article cited earlier:

Physicians typically used pestilentia, epidemia, and occasionally peste, but the word choice seems to have little significance.6 The words all conveyed a sense of large-scale mortality, without assigning any discrete or distinguishing characteristics other than death by illness.

[…]

In an extensive, careful survey of Italian, French, and German chronicles which were written during the mortality, Gabriele Zanella reviewed the classical and medieval sources to which the best known survivor narratives of the 1348 plague related.9 He observed that sustained consideration of the epidemic was quite rare in works written during 1348 or 1349. Zanella further emphasized that contemporary reports made in localities that were hit early were all situated within a larger context of crises—famines, war, earthquakes, and epidemic…

— 1 Universal and Particular: The Language of Plague, 1348–1500, by Ann G Carmichael

In this context, I’d like to especially recommend the first 20 min. of an unequalled documentary by Kate Sugak which explains how beginning in 13th century the term “plague” (Lat., pestis) took on the stigma of the previous label “leprosy”, both of which were used to denote non-distinct symptoms that were seen as punishment from God and were used by the Church and political authorities as reason for exiling or “quarantining”—i.e. imprisoning—whomever they judged as sinful, even cutting off entire towns so deemed.6

Furthermore, this idea of an abhorrent and sinful “disease” that could include (or not include) any of a large array of symptoms continued to be transmuted in ensuing centuries into the catch-all monickers “smallpox”, “syphilis” and, finally, “AIDS”.

This is one of the MOST THOROUGHLY RESEARCHED, WELL-PRESENTED AND ILLUMINATNG DOCUMENTARIES I’VE SEEN in four years of intensive research on disease.

Watch Sugak’s astounding documentary below!

Also on:

(Warning: The original is in Russian and the voice-over translation is buggy, apparently machine-produced.)

Summary: Takeaway Points to Remember

Cataclysmic, world-shaking events occur regularly since prehistoric times; these occurences may be more frequent than we’ve realized

Many of these events may have been provoked by cometary close encounters or meteor impacts

Fluctuations in solar activity can provoke abnormal volcanic and earthquake activity on earth; solar activity is itself also affected by comets

The 14th century saw high meteoric and cometary activity

Extreme volcanic emissions into the upper atmosphere beginning in the early to mid 13th century led to abrupt global cooling and disruption of the weather worldwide

Millennial floods and global cooling dramatically reduced farmland, in turn leading to wars over what remained

Cataclysmic events beginning in the early 1300s led to famine and disease, and climaxed in Europe during the years of the Black Death (1348-1351)

Seismic and or volcanic activity released poisonous gasses into the air, as related in contemporary accounts; these gasses had an extreme impact on people’s health, primarily the lungs

Skin symptoms such as boils or black-and-blue spots or streaks were sometimes though not always reported; even less frequently reported were lumps in the groin or armpits known as buboes

Pestilence or plague (Lat. pesti) was not a clearly defined disease but a catch-all term for illness leading to death

Widespread death was caused by many factors including famine, wars and respiratory poisoning; possibly even poisoned waters

Humans weren’t the only ones affected: many animals and fish also died; trees were stunted in their growth

(See also Hecker’s chronology in the Appendix)

1150-1300 - The Medieval Climate Optimum, a period warmer than today, sees fertility and population growth throughout Europe

1258-1259 - heavy volcanic activity coincides with the first major cold spell; 15,000 Londoners (30%) die in the famine of 1258 [Dobler]

1290 - desertion of previously cultivated farmland begins in Europe, a trend that will continue for 200 years

1298-1314 -seven large "comets" seen over Europe; one of "awe-inspiring blackness”. Many reports of foul smelling "mists" appeared continually after seeing bright lights in the sky, followed by an outbreak of the plague that coincided with the Great Famine in Europe [Dobler, p, 63]

1315 - Reduced area for farming due to colder climate led to failing food supplies that “triggered armed invasions and war for control of remaining croplands. The 1315 Flanders campaign of Louis X … who ruled large parts of today's France, was an example.” (source)

1315-1320 - cold, wet summers, alternating with years of drought, brings the Great Famine of Europe to a climax; famine carries away 30% of the population [Dobler]

1330 - Miraflores flood in the Atacama on the coast of Chile and Peru leads to the decline of the Chiribaya culture [Dobler 7.1.1]

1333 - drought and famine in China followed by torrential rains and flooding "in and about Kingsai [JiangXi?], at that time the capital of the empire"; 400,000 perish; Tsincheou "falls in"; Mt. Etna in Sicily erupts [Hecker]

1334 - flooding in Canton; drought followed by plague in Tche, 5 million die, earthquake around Kingsai; mountains of Ki-ming-chan fall in creating a lake 100 leagues (240-460 mi.) long; more drought, locusts, famine and pestilence [Hecker]

1336 - atmospheric disturbance and lightning storms in the north of France [Hecker]

1337 - drought in Kiang, 4 million die; deluges, locust, 6 day earthquake; swarms of locust appear in Franconia (Bavaria) the same year [Hecker]

1338 - 10 day earthquake in Kingsai; harvest failure in France [Hecker]

1340 - peak of cold, damp climate in Patagonia [Dobler 7.1.1]

1341 - flooding in southern India alters the course of the Periyar River [Dobler p.20]

1339-1342 - "in China, a constant succession of inundations, earthquakes and famine" [Hecker]

1342 - 1342 Three to four waves of floods of millenial proportions affect a large part of Europe, destroying farmland and altering the courses of rivers. [Dobler 3.1.2]

1343 - Hong-tchang mountain falls in, leading to a deluge; violent earthquakes in Egypt and Syria [Hecker]

1347 - more frequent earthquakes, famines and floods up to this year in China when "the fury of the elements subsided" there [Hecker]

March - violent eruptions of Mt. Etna, Sicily, cease, giving way to weak strombolian activity and pyroclastic flows (hot gas and ash) continuing into 1348 [Sezione di Catania - Osservatorio Etneo (INGV)]

August - comet “Negra” seen over France

October - Genoese galleys from “the east” arrive in Messina, Sicily, (just north of Mt. Etna via the Straight of Messina) with sick and dying men aboard (date questionable, source needed)

December - “pillar of fire” seen over the Pope's palace in Avignon, southwestern France

1348

January 25 - a great earthquake in Fuili, in the eastern Italian Alps affects towns as far south as Rome; a landslide and flood associated with the quake destroys Villach, Austria

August - a “big and bright star”, possibly a comet appears at dusk over Paris in the west and come nightfall breaks up into “rays” and disappears [Dobler p. 21]

1349 - plague spreads north into England and other northern European countries

1360 - “…destructive earthquakes extended as far as the neighbourhood of Basle, and recurred until the year 1360, throughout Germany, France, Silesia, Poland, England and Denmark, and much further north,” says Hecker. He ends his chronology by refering to forces from within the earth itself:

“In the inmost depths of the globe, that impulse was given in the year 1333, which in uninterrupted succession for six-and-twenty years shook the surface of the earth.”

Appendix:

Hecker’s incomplete but astounding chronology

In chapter 3 of J.F.C. Hecker’s 1832 book, Black Death , the learned German physician and professor gives an overview of the “mighty revolutions of the earth’s organism” in the 14th century, beginning his chronology with the year 1333, in China.

Hecker uses an old romanization of Chinese place names predating both pinyin and the Wade-Giles system and likely derived from local dialects which can be as different from each other as the languages of Europe. I’ve been unable to discover anything about these place names apart from that “King” in the old designation was used to refer to a dynasty which perhaps has something to do with Hecker’s “Kingsai”.

From China to the Atlantic, the foundations of the earth were shaken,—throughout Asia and Europe the atmosphere was in commotion, and endangered, by its baneful influence, both vegetable and animal life. The series of these great events began in the year 1333, fifteen years before the plague broke out in Europe : they first appeared in China. Here a parching drought, accompanied by famine, commenced in the tract of country watered by the rivers Kiang and Hoai. This was followed by such violent torrents of rain, in and about Kingsai, at that time the capital of the empire, that, according to tradition, more than 400,000 people perished in the floods. Finally the mountain Tsincheou fell in, and vast clefts were formed in the earth. In the succeeding year (1334)… the neighborhood of Canton was visited by inundations ; whilst in Tche, after an unexampled drought, a plague arose, which is said to have carried off about 5,000,000 of people. A few months afterwards an earthquake followed, at and near Kingsai ; and subsequent to the falling in of the mountains of Ki-ming-chan, a lake was formed of more than a hundred leagues in circumference, where, again, thousands found their grave. In Hou-kouang and Ho-nan, a drought prevailed for five months and innumerable swarms of locusts destroyed the vegetation ; while famine and pestilence, as usual, followed in their train… It is remarkable … that simultaneously with a drought and renewed floods in China, in 1336, many uncommon atmospheric phenomena, and in the winter, frequent thunder storms, were observed in the north of France ; and so early as the eventful year of 1333, an eruption of Etna took place. According to the Chinese annals, about 4,000,000 of people perished by famine in the neighbourhood of Kiang in 1337 : and deluges, swarms of locusts, and an earthquake which lasted six days, caused incredible devastation. In the same year, the first swarms of locusts appeared in Franconia, which were succeeded in the following year by myriads of these insects. In 1338, Kingsai was visited by an earthquake of ten days' duration ; at the same time France suffered from a failure in the harvest; and thenceforth, till the year 1342, there was in China, a constant succession of inundations, earthquakes, and famines. In the same year great floods occurred in the vicinity of the Rhine and in France, which could not be attributed to rain alone ; for everywhere, even on the tops of mountains, springs were seen to burst forth, and dry tracts were laid under water in an inexplicable manner. In the following year, the mountain Hong-tchang, in China, fell in, and caused a destructive deluge ; and in Pien-tcheou and Leang-tcheou, after three months' rain, there followed unheard-of inundations, which destroyed seven cities. In Egypt and Syria, violent earthquakes took place ; and in China they became, from this time, more and more frequent… Meanwhile, floods and famine devastated various districts, until 1347, when the fury of the elements subsided in China.

The signs of terrestrial commotions commenced in Europe inn the year 1348…

On the island of Cyprus, the plague from the East had already broken out ; when an earthquake shook the foundations of the island, and was accompanied by so frightful a hurricane, that the inhabitants who had slain their Mahometan slaves, in order that they might not themselves be subjugated by them, fled in dismay, in all directions. The sea overflowed—the ships were dashed to pieces on the rocks, and few outlived the terrific event, whereby this fertile and blooming island was converted into a desert. Before the earthquake, a pestiferous wind spread so poisonous an odour, that many, being overpowered by it, fell down suddenly and expired in dreadful agonies....

Never have naturalists discovered in the atmosphere foreign elements, which, evident to the senses, and borne by the winds, spread from land to land, carrying disease over whole portions of the earth, as is recounted to have taken place in the year 1348. …German accounts say expressly, that a thick, stinking mist advanced from the East, and spread itself over Italy … just at this time earthquakes were more general than they had been within the range of history. In thousands of places chasms were formed, from whence arose noxious vapours, and … it was reported, that a fiery meteor, which descended on the earth far in the East, had destroyed every thing within a circumference of more than a hundred leagues, infecting the air far and wide. The consequences of innumerable floods contributed to the same effect ; vast river districts had been converted into swamps ; foul vapours arose everywhere, increased by the odour of putrified locusts, which had never perhaps darkened the sun in thicker swarms, and of countless corpses, which, even in the well-regulated countries of Europe, they knew not how to remove quickly enough out of the sight of the living…

Now, if we go back to the symptoms of the disease, the trardent inflammation of the lungs points out, that the organs of respiration yielded to the attack of an atmospheric poison—a poison, which if we admit the independent origin of the Black Plague at any one place on the globe, which, under such extraordinary circumstances, it would be difficult to doubt, attacked the course of the circulation in as hostile a manner as that which produces inflammation of the spleen, and other animal contagions [i.e. poisons} that cause swelling and inflammation of the lymphatic glands.

Given thee context, the sense of the word “contagions” above would appear to be “poisons” or “harmful or corrupting influences” (see here).

Yet, despite giving ample evidence for a poison cause of plague, Hecker shows in chapter 2 that he is clearly a contagionist—he even thinks plague can be transmitted by a sick person casting his eyes on someone at a distance (!)—something that appears in 14th century accounts like de Mousi’s— but he seems to believe in a combination of environmental factors (especially poisonous winds) and human to human transmission. Notice how he first begins by saying that on Cyprus “the plague from the East had already broken out” before a great earthquake hit—by “plague from the East” he may be simply reflecting the fact that Europeans associated plague with “the East”—but later he goes on to tell that before the earthquake there was already “a pestiferous wind” causing people to drop dead. The account leaves a number of things unclear.

One cannot blame him for conflating environmentally induced illness and human to human transmission; although anticontagionists like Clot Bey were making waves in certain quarters during Hecker’s time (see Part 1), human contagion was still a dominant belief among traditionalists. What Hecker does excellently in this chapter is paint a picture of the extreme upheaval the earth was in at this time. And what you see in the above excerpt isn’t the half of it!

Continuing where we left off:

Pursuing the course of these grand revolutions further, we find notice of an unexampled earthquake, which, on the 25th of January, 1348, shook Greece, Italy, and the neighbouring countries. Naples, Rome, Pisa, Bologna, Padua, Venice and many other cities suffered considerably : whole villages were swallowed up. Castles, houses, and churches were overthrown, and hundreds of people were buried beneath their ruins. …[D]uring this earthquake, the duration of which is stated by some to have been a week, and by others a fortnight, people experienced an unusual stupor and head-ache, and that many fainted away. These destructive earthquakes extended as far as the neighbourhood of Basle, and recurred until the year 1360, throughout Germany, France, Silesia, Poland, England and Denmark, and much further north. Great and extraordinary meteors appeared in many places, and were regarded with superstitious horror. A pillar of fire, which on the 20th of December, 1348, remained for an hour at sunrise over the pope's palace in Avignon; a fireball, which in August of the same year was seen at sunset over Paris…

The order of the seasons seemed to be inverted,—rains, floods and failures in crops were so general, that few places were exempt from them…

[…]

Diseases, the invariable consequence of famine, broke out in the country, as well as in cities ; children died of hunger in their mothers' arms,—want, misery and despair, were general throughout Christendom.

Such are the events which took place before the eruption of the Black Plague in Europe.

[…]

In the inmost depths of the globe, that impulse was given in the year 1333, which in uninterrupted succession for six-and-twenty years shook the surface of the earth, even to the Western shores of Europe.

Tobin Owl is an independent researcher/writer. Over the past four years he’s conducted in-depth investigation focusing on the history of modern medicine, medical science, geopolitical conspiracy and the environment. Articles written prior to his move to Substack are found on his website Cry For The Earth

Notes:

Maya Creation Myths: Words and Worlds of the Chilam Balam by Timothy W. Knowlton tells how “an anonymous Maya scribe penned what he called u kahlay cab tu kinil (“the world history of the era”)... In this he collected numerous accounts of the cyclical destruction and reestablishment of the cosmos.”

Aztec mythology tells of five worlds, known as the Five Suns, saying the present world is the fifth. The first Aztec world was destroyed by jaguars (perhaps comets, similar to the Euopean stories of fire-breathing dragons?), the second by hurricanes and floods, the fourth by a rain of ashes and fire (meteor explosions/volcanes?), the fourth by a great flood. Notably each world is said to have lasted 676 years, (with the exception of the third which lasted 384 years

B.G. Babington’s translation of Hecker’s Black Death cited in this article (see Appendix) speaks of a lake 100 leagues in circumfrence, not 100 leagues “long.” This is comparable to the sized of Lake Issyk Kul in present day Kygystan, one of the largest and deepest lakes in the world. Although said to be of tectonic origin, it long predates the 14th century, and even though ruins of a city and a monastery are found beneath it’s waters, I haven’t found specific reference to the period under discussion. A legend that a palace built by the Mongol-Turk lord Tamerlane (Timur the Lame, 1370-1405) was inundated there after his death points to a time too late to fit with Hecker’s account.

Dobler, p. 14, cites the following:

“In China, already the 13th century Mongol conquest disrupted farming and trading, and led to widespread famine starting in 1331 with plague arriving soon after. The population dropped from approximately 120 to 60 million.” [Ping-ti Ho, "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China", in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970) pp. 33–53.]

“The 14th century- plague killed an estimated 25 million Chinese and other Asians during the 15 years before it entered Constantinople in 1347.” [Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present. Infobase Publishing. p. 31.]

Information about strombolian activity in 1347 came from AI, which is not totally to be trusted. AI attributed the information to Sezione di Catania - Osservatorio Etneo (INGV)

According to Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, the word “plague” was first used in the 14th century in the sense of 1a: a disastrous evil or affliction : CALAMITY. It was only occasionally used in contemporary accounts in reference to what was then then more commonly called in English “The Great Mortality”, “The Great Pestilence” or sometimes “The Universal Pestilence.”

Kate Sugak, who speaks primarily Russian, is more likely referring to the Latin term pestis. During the 13th century, pestis began to emerge as a distinct medical concept to describe the plague. The development of university medicine, the rise of medical texts, and the Latinization of medical terminology during this period laid the groundwork for its adoption and continued use throughout the Middle Ages and beyond.

The term “plague” in specific reference to Bubonic plague did not arise until the 18th century with Thomas Snydham. The same century saw the first appearance of the term “Black Death” in specific reference to the Great Mortality of 1347-1351.

Incredible research. It's very clear that mass disease breakouts are environmental in nature and not contagions.

Great Chicago fire populary attributed to Mrs o'leary's cow kicking over a lantern happened on the same day as the great fire that consumed the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin. Meteor shower as an alternate explanation.